At 6 in morning, after having gotten breakfast at McDonald's, and not having gone to bed yet, we finished with peggy plan b, brought Simon over, and marveled in our craft.

Rachel still fit perfectly in his cold metallic arms.

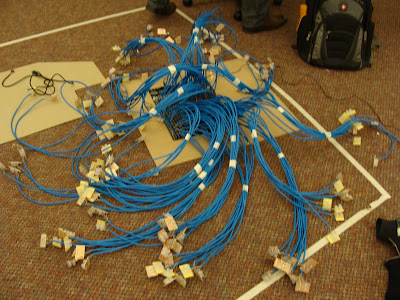

So after having had slept for a couple hours, we rejoined forces to finish putting Simon together, and to install him in all of his glory in the gallery. John took this picture, and I still feel like we build a sacrificial alien alter. I don't see the correlation between this, and the robotic creature we intended to make people happy with.

In presentation, Simon did not move, had a limited color mixing display on his belly, didn't talk, didn't nod, didn't tweet, didn't make you warm, didn't harvest energy from the sun, didn't nothin.

Basically Simon was our dumbsurface, our "Downs Surface" as Eric liked to say. He was far more complex than we could have ever guessed, especially when it came down to trying to get the camera to talk to the motors or the aruino, and fighting with Peggy for days. I think we're fortunate it didn't collapse under it's own weight, the steel brackets Eric put in (I helped) really made a difference on the stability front.

When we presented, one of our guests, who was more than skeptical of all of the projects, and voiced his skepticism quite thoroughly, pointed out that our surface did essentially nothing, and he would never consider our project a success. While I agree, in what we set out to do, we really didn't accomplish any of "Sustainability for happiness" goals, but the project wasn't a waste of time and money. I didn't sleep three hours a night for three weeks, and struggle to keep up in my other classes because I was focusing almost singly on this project, to not feel like something was gained.

We made a 6 foot tall robot, who, until five minutes before we presented, did in fact move. For proof, please view this video. Rachel and I were definitely making embarrassingly excited noises